- 36 Labeling Emotionsdialectical Behavioral Training Reliaslearning

- Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Definition

- What Is Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

- Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Dbt Techniques

- Training Courses Dialectical Behavior Therapy

36 Labeling Emotionsdialectical Behavioral Training Reliaslearning

- OSHAcampus has been a top OSHA safety training provider since 1997. 100% online OSHA training certifications. Stay at home & practice social distancing!

- “The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Workbook update, by McKay, Wood, and Brantley, is remarkable in the attention it gives to explaining DBT skills, and in providing directions about how to practice and use the skills that are easy to follow. They have connected the skills in a way that makes sense, and that makes them understandable.

Summary: The internet is increasingly used to gain knowledge and understanding of a topic. This knowledge is often acquired accidentally, as a byproduct of browsing. Critical internet use is becoming social.

The web has changed dramatically over the last two decades. To understand how user behavior has been affected by these changes, we replicated a 1997 study conducted at Xerox PARC. We asked people to describe a situation where online information significantly impacted their decisions or actions.

We found that, compared to 22 years ago, a larger proportion of current critical internet activities involved finding answers and gathering information in order to better understand a topic. A fair amount of information was acquired in a passive way, without looking for it, during browsing. And often, during critical activities, users turned to other people, asking for their help or opinion.

NOTE: Person Growth Worksheets will not be used as homework. These are for your use only. Please DO NOT Submit any filled in sheets in Lesson Group.

Methodology

Original Study (1997)

In 1997, Julie Morrison, Peter Pirolli, and Stuart Card conducted a large-scale survey with 3,292 respondents in which they asked people to answer a single question:

Please try to recall a recent instance in which you found important information on the World Wide Web, information that led to a significant action or decision. Please describe that incident in enough detail so that we can visualize the situation.

This question was intended to study important web use, rather than all web use. It’s an example of a UX-research method called the critical-incident technique: participants are asked to recall a significant event that has a certain quality. In this case, the question focuses on web use that influenced actions or decisions that people considered important — such as making a purchase, interacting with a company, or changing an opinion.

The Xerox PARC researchers organized the responses in three different taxonomies:

- the purpose of the activity reported in the incident: Find, Compare/Choose, and Understand

- the method used to find information: Find, Collect, Explore, and Monitor

- the domain of the content that was consumed: Business, Education, Finance, Job search, Medical, Miscellaneous, News, People, Product Info & Purchase, and Travel

Replication Study (2019)

Since 1997, there were at least three major web-related changes likely to influence usage patterns:

- Many more people access the internet today than in 1997. According to ITU, only 2% of the world’s population had internet access in 1997. This proportion was estimated to be 54% in 2019. In the United States, internet access is even more widespread: according to Statista, 87% of people in the US had access to the internet in 2019, compared with 36% in 1997 (according to Pew).

- Today, people access the web on a variety of devices — mobile phones and tablets being among the most notable. In 2019, We Are Social reported that people spent 48% of their online time on mobile phones. In contrast, in 1997, virtually all web use was on desktop computers (in our first study of mobile web use in 2000, most users said that phones were not ready for the internet).

- There are many more services available on the internet today than in 1997 (between the two studies, the number of websites grew from about 1 million to about 183 million — to say nothing of the millions of apps available in the Apple and Android app stores).

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Definition

These changes mean that the internet is more readily accessible today than in 1997, both in terms of audience size and where and when people go online. It’s only natural to expect that that important information-seeking behavior may have changed as well.

In order to test this hypothesis, we decided to replicate and expand the 1997 Xerox PARC study. We started with the same question that was asked in that study, but, after several rounds of pilot testing, we had to slightly modify the wording of the original question. In 1997, people performed relatively few online information-seeking tasks in their recent past, so it was easy for them to choose a single instance. Today, our respondents were performing hundreds of such tasks in a single day, so isolating one was difficult.

Here’s the question that we used in the final survey:

Please try to recall a recent instance in which you found important information online, information that led to a significant action or decision. Please describe that incident in enough detail so that we can visualize the situation.

If you can recall several such instances, please describe the one that was the most important to you.

(Research purists will note that modifying the wording means that our study wasn’t a true replication of the original. However, an exact replica of the old study wasn’t interesting, because the usual goal of research replication is irrelevant in this case. Usually, studies are replicated to assess the validity of the findings. But, our goal was not to confirm or refute the original — an impossible feat given the 22 years between the studies — but rather to assess the current state of internet use. It’s also possible — even though highly unlikely — that any differences between the two studies are due to the slight variation in wording instead of the time distance between them.)

We followed up this core question with several other questions meant to clarify the context of the reported information-seeking task:

- Satisfaction scores and comments: How satisfied respondents were with the websites or the applications they had used and what changes they would have liked to make, if any.

- Context: When and where the reported instance happened, what device(s) was used, and whether the user interacted with anyone else.

- Importance: How much their decision was influenced by the information they had found online. (We removed respondents who selected Not at all because we wanted to capture only influential information acquisition.)

Our online survey received 750 responses. We collected the data over two separate periods: weekdays and weekend. We split the data collection to avoid time-related biases. (For example, it’s possible that during the week most important tasks are work- or school-related.)

We substantially overrecruited, anticipating that many of the responses would not be detailed enough for coding. We ended up including 498 of the responses in our analysis.

We strictly coded the answers based on the criteria set by the Xerox researchers and came up with new categories only when the answers didn’t fit any existing ones, to ensure that the two studies were comparable. One researcher coded the full dataset and a second researcher coded 100 randomly selected responses. The definitions of new categories were discussed afterwards, and the first researcher recoded all the responses based on the discussion.

We also came up with two additional taxonomies (Social Interaction and Device) that reflected the new web landscape and practices in which web users engage today.

In what follows, we discuss all these different taxonomies (old and new) separately.

Purposes of Web Activities: More Understand Activities

In the original study, researchers grouped important information-seeking behaviors in 3 categories, reflecting the purpose of the activity:

- Compare/Choose: The user evaluates multiple products or information sources to make a decision. For example, one participant compared the prices and features of several pieces of specialized scientific equipment in order to decide which one to purchase.

- Understand: The user gains understanding of some topic. For instance, one participant reported that he decided against starting the Keto diet based on the information that he had found online.

- Acquire: The user looks for a fact, finds product information, or downloads something. For example, one participant looked up the steps to perform CPR. (The original study called this category Find.We chose to rename it, because the Xerox PARC researchers used the same label again elsewhere with a different meaning.)

Our data indicates that today’s web users engage more frequently in Understand information-finding activities and less in Compare/Choose activities than before. In the 1997 study, only 24% of the activities fell in the Understand category; in contrast, in our study this category received most responses (40%). (The difference was statistically significant, p < 0.001).

In 1997, the most popular category, accounting for more than half of the responses (51%), was Compare/Choose. In our study, only 36% of the responses were classified as Compare/Choose. (This difference was statistically significant, p < 0.001.) The third category, Acquire, comprised 24% of responses (similar to 1997, which was 25%).

The increase in Understand responses may be due to the fact that online content has become comprehensive and easy to access due to search improvements. Back in 1997, if you wanted to learn about a topic, you would probably have gone to the library, but today most people would just look it up online.

Why did the proportion of Choose/Compare activities decrease since 1997? This may be an artifact of our coding approach. We found that our survey participants often engaged in activities that fell in multiple categories; for example, a user reported “I researched what could help with psoriasis and then I bought a cream that I found online.” Though the primary purpose was to research the topic, it is likely that he also compared and chose from several options, though a possible comparison between different creams was not mentioned explicitly. Our code captured only the primary purpose that users stated clearly and had a critical influence on their decisions or actions.

So it isn’t that the proportion of Compare/Choose activities has necessarily decreased, but rather that the Understand activities have become more common than in 1997 and that Compare/Choose behaviors are now often an immediate consequence of Understand.

Content Types: Wider Variety of Important Online Content

In agreement with our finding that Understand activities have become more prevalent, we also found that the content that people viewed as critical had become broader, falling into 13 distinct content categories, compared to only 10 in the original study (which were transformed into 9 categories in our classification, after combining 2 of the original categories). In our study, 14% of the responses fell into the 4 new content categories that we identified.

The new content categories were Entertainment, Hobbies & Interests, Home & Families, and Pets. We combined the original Business and Job Search categories into a new category, Work. We also broadened and renamed the Medical category as Health and the Travel category as Planning.

Content Taxonomy and Examples

Categories | Examples |

Education | I searched for grad school online. I went through as many google search pages as possible. Over 25 pages before I started sending query emails. |

Finance | I researched best travel credit cards. I started with travel bloggers that I follow, to websites like NerdWallet and continued my research further to make my decision. |

Health (former Medical) | I researched and found a new dermatologist whose office accepted my new insurance. |

News & Politics | Found information regarding a new voting process. |

People | I found out that my friend has passed away and then attended the funeral. |

Planning (including event scheduling — former Travel) | I researched travel options online and decided to go with Airbnb instead of hotels. |

Product Info & Purchase | Researched the best kayak for me then made a purchase. |

Work | I was searching for a job and got to know about the job where I am working currently. |

Entertainment (new) | I looked up a movie on Flixster which determined the movie I went to by watching the trailer and then looking up the playing times available. |

Hobbies & Interests (new) | I was trying to set up a YouTube channel, and searched various tips and tricks for video editing. I created about ten using a software I had purchased. |

Home & Families (new) | We were evaluating our cable/internet service. We researched options online to determine the best fit for our needs. |

Pets (new) | Recently researched different dog breed prior to acquiring my golden retriever. |

Miscellaneous (content that does not fall in other categories) | I found out the process for renewing my auto registration and how to update my address with the DMV. |

Overall, Product Information & Purchase was the type of content most often mentioned (30% of all responses), followed by Health (19%). The results didn’t change significantly compared with the 1997 study, when 30% of the responses fell into Product Information & Purchase and 18% of the responses were classified as Medical. Though the Internet has grown a lot, it’s remarkable that these two main content categories still were involved in almost half of reported critical incidents.

In contrast, the Work and People categories saw major drops from the old study to the new. It’s probably not the case that respondents work less today but Work as a percentage of all critical internet use has dropped because there are now so many more options for nonwork use. The drop in People from 13% to 3% is partly (but only partly) compensated by the 7% of cases falling into the new Home & Family category, since some of the family-oriented use might previously have been considered people-oriented.

We observed that certain content types tended to be associated with specific purpose categories. For example, for Product Information & Purchase, 47% of the reported activities fell into the Compare/Choose category, but 75% of the Health responses belonged in the Understand category.

How the Information Was Acquired: The Growth of Passive Information Acquisition

The 1997 study reported 4 different ways in which the information was gathered: two categories (Find, Collect) were active and usually driven by an explicit information need that the user had (e.g., a specific question) and the other two categories (Explore, Monitor) were passive, meaning that the user was not actively seeking out the information. Explore activities referred to finding the information accidentally while browsing the web, without actively looking for it (e.g., a user found out about graffiti on Venice Beach while reading news and went out to clean it), while Monitor activities involved repeatedly going to a website in order to check for new or updated information.

In both studies, the majority of the information was accumulated through active methods, but we found that a larger proportion of the reported instances in the new study involved passive information acquisition (14% versus only 4% in 1997 — the difference was statistically significant, p < 0.05).

We found that Monitor activities were virtually nonexistent in 2019 — possibly because people did not provide us with enough information in order to determine whether they had visited the site repeatedly or not.

Instead, we identified another type of passive information acquisition: notifications (grouped in the new category Notified). Activities in this category were triggered by notifications — received through text and email messages or push notifications on smartphones (e.g., a user reported “Fandango sent me an alert saying that they had an early showing for Shazam, so I told my friends, and we immediately got tickets”). However, Explore activities still had the largest share among the passive information acquisition (83%); only 17% of the reported passive incidents fell into Notified.

Social-Interaction Patterns

In our study, we also asked users whether they interacted with anyone during the reported incident. We divided responses into 6 different categories; this taxonomy was not present in the original PARC study.

Social-Interaction Taxonomy and Examples

Categories | Definitions | Examples |

Collaborate | Work together with others during information seeking or decision making; each person has a say in the final decision. | I was shopping with my parents and we collectively decided to leave and go to Total Wine. |

Inquire | Ask someone for more information; the person doesn't have a say in the final decision. | I emailed the company by filling out a form on the website and they responded back by the next day with very in-depth information. |

Informed | Be informed by others via online means. | Tennis balls are not good for dogs, a friend lost her dog, we got rid of all tennis balls. It was a chat with friends on Facebook. |

Share | Inform others. | I shared the information with the friend who supplied me with the apricots, via email. |

Execute | Carry out an action through social interaction. | I called to make my purchase. |

No interaction | No social interaction mentioned at all by the respondents. |

28% of respondents reported accompanying social-interaction behaviors while making important decisions based on online information. Inquire was the most reported social-interaction activity (15%); the other types of social interaction were relatively low (under 6%).

Social-interaction patterns also showed a relationship with the type of content involved in the activity. For Product Info & Purchase decisions, though only 20% of instances had accompanying social-interaction behavior, 67% of their social interaction was Inquire. This makes sense — someone trying to make a decision about a purchase may have specific questions for a company representative or an existing customer.

In contrast, for News & Politics, 39% of responses reported accompanying social-interaction activities, but all of them were Share. For example, a respondent saw a blizzard warning in her city and shared the information with her mom: “I talked to my mom on the phone who lives in a different state to let her know not to worry since it was all over the news.”

Device

What Is Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

Another taxonomy that was new to the 2019 study referred to the device used during the reported incident. We defined 4 categories: desktop/laptop computers, smartphones, tablets, and multiple devices.

We found that most of the critical incidents (42%) occurred when people were using their smartphones — critical smartphone use was higher than critical desktop use (p < 0.05), which was somewhat surprising. (This result seems to contradict our finding that the activities done on mobile are rated as less important than those carried out on computers; the reason for this difference likely lies in the fact that smartphones are available at all times and tend to be used more than bigger devices — thus, it’s possible that it was easier for people to remember activities performed on a smartphone than activities performed on a computer.)

Only 6% of respondents relied on tablets to get online information to make important decisions. Multiple-device usage was also common, with 20% of our respondents using 2 or more devices during their incidents.

Different content types tended to be associated with different devices. For example, for the Product Info & Purchasecontent type, the distribution of device usage was relatively even: 39% smartphone, 29% desktop/laptop computers, and 24% multiple devices. In contrast, for the content type Health, 54% of the decisions were based on the information found on mobile phones. Most Work activities (more than 50%) were carried out on desktop/laptop computers.

Conclusion

Information technology has changed dramatically since 1997. But has user behavior? And in particular, has the impact of the internet on our lives changed in any ways? Our study has determined that the Internet has become a primary, influential source of information — the majority of the activities that people carry out on the internet are related to gathering knowledge and understanding a topic. 22 years ago, most important, memorable Internet-related activities involved comparing and choosing among different products or sources of information in order to make a decision. Even though these types of activities are still very present today, they are often a byproduct of educating ourselves and gathering knowledge about a topic. Also interestingly, a good chunk of the information we gather on the internet is passive — we’re not even looking for it, it’s simply delivered to us by virtue of notifications or discovered accidentally during browsing. (The passive information gain is possibly related to the Vortex — as we’re spending more and more time on the internet, jumping from one site to the next, we inherently discover more information that we’re not looking for.)

We also discovered that today, critical-internet usage is often a social activity — it involves more than one person. That’s likely due to the ubiquity of smartphones: everyone is always connected, within one-tap reach, and can quickly chime in with an opinion or with a piece of information whenever needed. (Also, there are many more services now for connecting with other people through technology.) Last, but not least and not surprisingly, many, many critical activities are carried out on phones today. It’s not the case that people will do every type of task on a small screen, but many of the important and memorable tasks are done (or at least partially done) on their phone. The ability to start an activity on one device and seamlessly continue it on another is, thus, crucial for a good user experience.

Given the growing importance of information-gathering activities, a big implication is that sites need to go beyond merely providing alternatives to users and focus on providing good content that educates them. Content is why users come to your site. Even on an ecommerce site, appealing visual design won’t persuade users to purchase — but comprehensive content that clearly and understandably explains product benefits will. Good and credible content can help users gather the information they want quickly and further increase their awareness of your brand.

A final point relates to the concept of critical use, as opposed to average use. Many methods to analyze what users do on a website will be dominated by less-important use cases, since average problems tend to occur more frequently than truly important ones. Thus, if you only go by pure statistics, you may end up designing to support people’s less important needs and provide poor (or nonexistent) support for their most crucial needs. We strongly recommend that you conduct research to gain an understanding of your customers’ most important needs and design with those in mind, even if they are not as frequent.

Reference

Morrison, J.B., Pirolli, P., and Card, S.K. (2001): 'A Taxonomic Analysis of What World Wide Web Activities Significantly Impact People's Decisions and Actions.' Interactive poster, presented at the Association for Computing Machinery's Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seattle, March 31 – April 5, 2001. (Warning: link leads to a PDF file.)

MARSHA M. LINEHAN, Ph.D. is the originator of Dialectical Behavior Therapy and is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington.

NOTE: Writing of this manuscript was partially supported by grants MH34486 and DA08674 from the National Institutes on Mental Health and Drug Abuse, respectively, Bethesda, Maryland.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) represents a major health problem for the 1990s and beyond. It is a prevalent disorder that is severe, chronic, and persistent. The number of individuals meeting criteria for the disorder is high, approximately 11% of all psychiatric outpatients and 20% of psychiatric inpatients. In addition to being prevalent, follow up studies consistently indicate that the diagnosis of BPD is chronic. Between 57 and 67% continue to meet criteria four to seven years after the first diagnosis and up to 44% continue to meet criteria fifteen years later.

The severity of BPD is perhaps best seen in the high mortality rate of the disorder. Approximately 10% of BPD patients eventually die by suicide. The suicide rate is much higher among the 36 to 65% of BPD individuals who have attempted suicide or otherwise injured themselves intentionally at least once in the past. Looking at suicide rates from the reverse angle, 12 to 33% of all individuals who die by suicide meet criteria for BPD. The emotional costs of BPD are enormous. BPD individuals describe chronic feelings of anger, emptiness, depressions and anxiety. They experience extreme frustration and anger, and occasionally experience brief psychotic episodes. They describe chaotic relationships and 'confused identities.' Even among those who have not attempted suicide, suicide ideation is common. The quality of life ratings for some of the problems frequently experience by BPD individuals suggest that their quality of life is amongst the lowest.

At present there are very few treatments with proven efficacy in treating BPD individuals. In summarizing the findings of pharmacological treatment studies, Paul Soloff, MD., concludes that pharmacotherapy effects, while clinically significant, are nonetheless modest in magnitude. The empirical evidence supporting psychosocial treatments for BPD is similarly meager. This poses a special problem because even when effective pharmacotherapy is given, the complexity and severity of BPD dictates concurrent psychotherapy. To date cognitive-behavioral therapy (specifically, Dialectical Behavior Therapy or DBT) is the only treatment that has been shown in controlled clinical trials to be effective treating BPD.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Foundations

DBT is based on a model suggesting that both the cause and the maintenance of BPD is rooted in biological disorder combined with environmental disorder. The fundamental biological disorder is in the emotion regulation system and may be due to genetics, intrauterine factors before birth, traumatic events in early development that permanently affect the brain, or some combination of these factors. The environmental disorder is any set of circumstances that pervasively punish, traumatize, or neglect this emotional vulnerability specifically, or the individual's emotional self generally, termed the invalidating environment. The model hypothesizes that BPD results from a transaction over time that can follow several different pathways, with the initial degree of disorder more on the biological side in some cases and more on the environmental side in others. The main point is that the final result, BPD, is due to a transaction where both the individual and the environment co-create each other over time with the individual becoming progressively more emotionally unregulated and the environment becoming progressively more invalidating.

Emotional difficulties in BPD individuals consists of two factors, emotional vulnerability plus deficits in skills needed to regulate emotions. The components of emotion vulnerability are sensitivity to emotional stimuli, emotional intensity, and slow return to emotional baseline. 'High sensitivity' refers to the tendency to pick up emotional cues, especially negative cues, react quickly, and have a low threshold for emotional reaction. In other words, it does not take much to provoke an emotional reaction. 'Emotional intensity' refers to extreme reactions to emotional stimuli, which frequently disrupt cognitive processing and the ability to self soothe. 'Slow return to baseline' refers to reactions being long lasting, which in turn leads to narrowing of attention towards mood congruent aspects of the environment, biased memory, and biased interpretations, all of which contribute to maintaining the original mood state and a heightened state of arousal.

An important feature of DBT is the assumption that it is the emotional regulation system itself that is disordered, not only specific emotions of fear, anger, or shame. Thus, BPD individuals may also experience intense and unregulated positive emotions such as love and interest. All problematic behaviors of BPD individuals are seen as related to re-regulating out of control emotions or as natural outcomes of unregulated emotions.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy: The Treatment Model

DBT assumes the problems of BPD individuals are twofold.

First, they do not have many very important capabilities, including sufficient interpersonal skills, emotional and self regulation capacities (including the ability to self regulate biological systems) and the ability to tolerate distress.

Second, personal and environmental factors block coping skills and interfere with self regulation abilities the individual does have, often reinforce maladaptive behavioral patterns, and punish improved adaptive behaviors.

Helping the BPD individual make therapeutic changes is extraordinarily difficult, however, for at least two reasons. First, focusing on patient change, either of motivation or by teaching new behavioral skills, is often experienced as invalidating by traumatized individuals and can precipitate withdrawal, noncompliance, and early drop out from treatment, on the one hand, or anger, aggression, and attack, on the other. Second, ignoring the need for the patient to change (and thereby, not promoting needed change) is also experienced as invalidating. Such a stance does not take the very real problems and negative consequences of patient behavior seriously and can, in turn, precipitate panic, hopelessness and suicidality.

It was the tension and ultimate resolution of this essential conflict between acceptance of the patient as he or she is in the moment versus demanding that the patient change this very moment that led to the use of dialectics in the title of the treatment. In DBT, treatment requires confrontation, commitment and patient responsibility, on the one hand, and on the other, focuses considerable therapeutic energy on accepting and validating the patient's current condition while simultaneously teaching a broad range of behavioral skills. Confrontation is balanced by support. The therapeutic task, over time, is to balance this focus on acceptance with a corresponding focus on change. As a world view, furthermore, dialectics anchors the treatment within other perspectives that emphasize:

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Dbt Techniques

1. the holistic, systemic and interrelated nature of human functioning and reality as a whole (asking always 'what is being left out of our understanding here?');

2. searching for synthesis and balance, (to replace the rigid, often extreme, and dichotomous responses characteristic of severely dysfunctional individuals);

3. enhancing comfort with ambiguity and change which are viewed as inevitable aspects of life.

DBT is designed to address the following five functions of successful treatments:

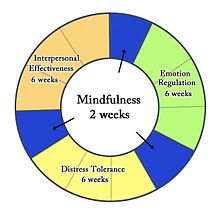

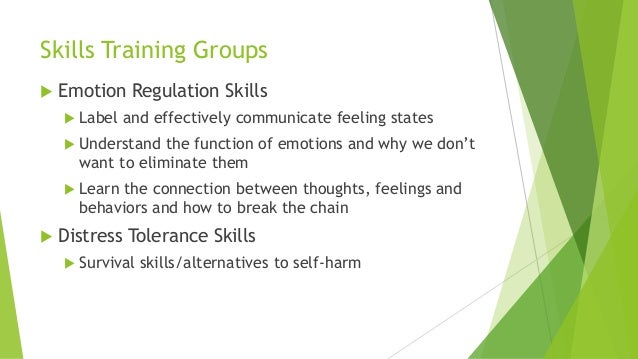

Capability Enhancement focuses on increasing behavioral and self regulation. All patients in DBT receive psycho-educational skills training in five areas: mindfulness (to improve control of attention and the mind), interpersonal skills and conflict management, emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and self management. Medications are also used here for enhancing the individual's ability to self regulate biological systems.

Training Courses Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Motivational Enhancement focuses on making sure that clinical progress is reinforced (rather than punished), that maladaptive behavior is not reinforced, and on reducing other factors (such as emotions or beliefs) that inhibit or interfere with clinical progress. Generally, this requires intensive (at least weekly sessions of one to one and a half hours) individual therapy. The full range of effective cognitive and behavioral therapies are integrated into the treatment targeting in order of importance: reducing suicidal and other life threatening behaviors; reducing therapy-interfering behaviors (including noncompliance and dropping out of treatment); reducing sever quality of life interfering behaviors (including Axis I disorders, such as depression and eating or / and substance abuse disorders); increasing skillful coping behaviors, including distress tolerance emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and mindfulness; reducing traumatic emotional experiencing, including post-traumatic stress responses (for example, continuing reactions to childhood trauma); enhancing self-respect and mastery and reducing problems in lying; and resolving a sense of incompleteness.

Enhancing Generalization. Learning to be effective in a therapist's office or an inpatient or residential setting is useless if the new behaviors do not generalize to the patient's everyday life settings. The third task of therapy, therefore, is to ensure generalization of new behaviors to the natural environment. In DBT this is generally done by phone consultations between patient and individual therapist. In inpatient, residential, and day treatment settings this might be done by on site consultants with 'office hours' for skills consultation.

Enhancing Therapist's Capability and Motivation. An effective treatment is useless if the therapist is unable or unmotivated to apply the treatment when it is required. Enhancing the therapist's capabilities and motivation to treat effectively is an unrecognized but essential part of any treatment program. In DBT, this function of treatment is met by weekly team consultation meetings of all DBT therapists. The goal of these meetings is to provide consultation and support for therapists in their attempts to apply DBT.

Treatment strategies are divided into four main groups as follows. Dialectical strategies consist of balancing acceptance and change in all interactions, always searching for a synthesis and looking to shift the frame of problems that resist solution. DBT core strategies require the balancing of validation with problem solving. Validation consists of a set of strategies emphasizing acceptance and validation of the patient by listening empathetically, reflecting accurately, articulating that which is experienced but not necessarily said, clarifying those disordered behaviors that are due to disordered biology or past learning history, and highlighting those behaviors that are valid because they fit current facts or are effective for the patient's long term goals. The essence of validation is seeing and responding to the patient as a person of equal status and value. Problem solving strategies are designed to assess the specific problems of the individual, figure out what factors are controlling or maintaining the problem behaviors, and then systematically applying behavior therapy interventions.

Structuring the Environment. If the environment continues to reinforce problematic and borderline behaviors and punishes clinical progress, then it is useless to expect that treatment gains will be maintained once treatment is ended. Thus, if treatment is to end, the therapy must assist the patient in developing an environment that is maximally supportive of clinical gains. It is equally important that the therapist focus on providing a treatment atmosphere that encourages progress and does not encourage relapse. Family sessions and case consultation meetings with other therapists (always with the patient present) serve this function in DBT.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Effectiveness

DBT has demonstrated effectiveness in two controlled randomized clinical trials. In the first study conducted by myself and my colleagues at the University of Washington, 47 chronically suicidal BPD patients were randomly assigned for a year either to DBT or to referral to treatment as usual in the community. During the year, DBT patients were less likely to attempt suicide or drop out (84% remained in treatment). They spent much less time in psychiatric hospitals, had greater reductions in use of psychotropic medications, and were better adjusted at the end of the year. They were also less angry than patients given standard psychotherapy (although at one year not less depressed or less likely to think about suicide). Most of these differences persisted a year after treatment ended.

It could be argued that DBT patients had a better outcome simply because they received more psychotherapy than the others. But DBT proved to be more effective even after researchers corrected for the amount of time spent with psychotherapists, and even after they excluded patients who received no individual psychotherapy. We are now conducting a large randomized clinical trial of DBT with a new group of therapists and patients. Preliminary results suggest that DBT is effective in this replication study as well.

In a just completed study here at the University of Washington, 23 drug abusing BPD women were assigned to DBT or to referral to treatment as usual in the community. At the end of the one year treatment, use of illicit drugs was lower and attendance at treatment was higher in the patients who got DBT versus those referred to treatment as usual in the community. In several studies researchers at other institutions have partially replicated our results. They have found less suicidal behavior among patients given DBT than among similar patients given a different treatment. These were not true controlled studies, however, since the patients were not assigned to treatment condition (DBT versus non-DBT treatment) at random. Thus, it will be very important to replicate these studies using more rigorous research methods.

The intense suffering that accompanies borderline personality disorder, both for the patient and for the community surrounding the patient, suggest that a high priority must be put on both developing new more effective treatments and on dissemination of those that are currently available. This is especially true in community mental health where in some states the lack of improved outcomes with some treatments have led those controlling reimbursement to refuse to treat or pay for treatment for BPD patients. Although a case might be made for some that an ineffective treatment is more harmful than no treatment, the same cannot be said for treatments that have been shown to be effective in rigorous clinical trials.